Is Circularity the Solution to Africa’s Rapid Urbanization?

Photo: Till Müllenmeister.

Photo: Till Müllenmeister.

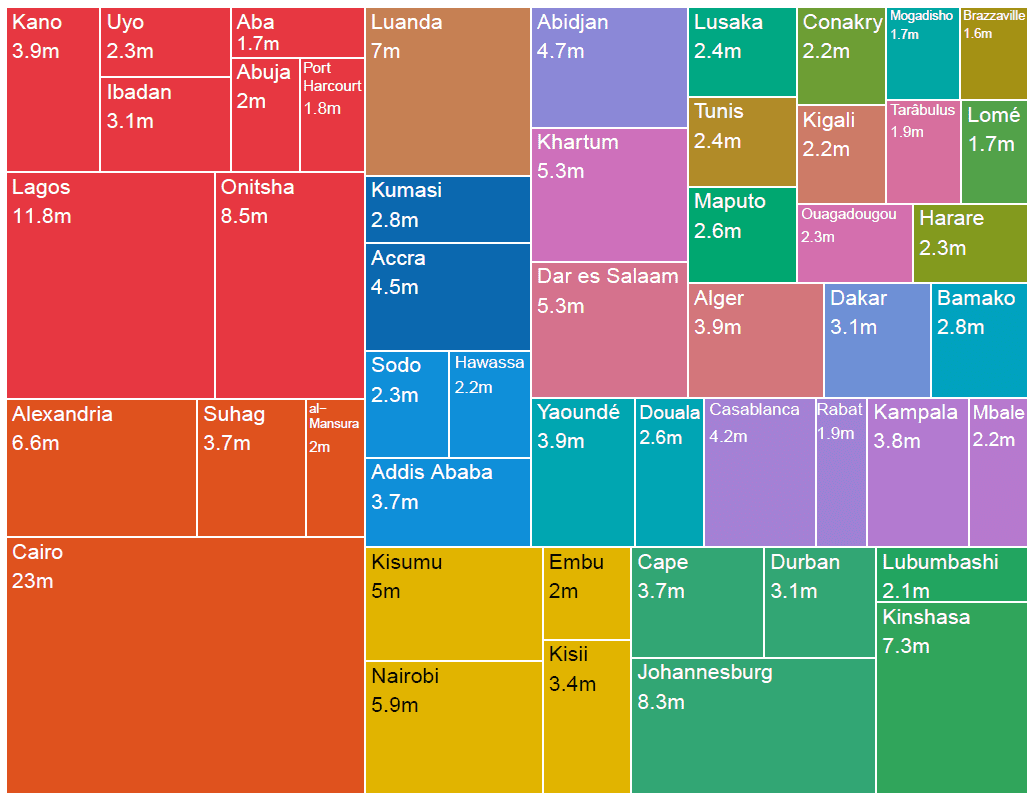

OECD data shows five large urban agglomerations of global business, media and policy-making in Africa: Cairo and Lagos are the two biggest, followed by Onitsha, Nigeria. With 8,5 million inhabitants, a large urban area is emerging, driven by growth and the merging of built-up areas to form one large agglomeration. With 8,3 million and 7,3 million inhabitants respectively, Johannesburg and Kinshasa, are the 4th and 5th biggest.

The OECD’s recent report on the circular economy in cities says that cities and regions have a key role to play as “promoters, facilitators and enablers” of circular economy. That report, however, focuses almost exclusively on cities in the Northern hemisphere. It is based on findings from 51 cities and regions in the industrialized world, and on lessons learnt from policy dialogues in six cities in the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain, the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The draft discussion paper “Circular Cities in Africa – A reflection piece by Africans about Africa” aims to fill the gap. It was convened by the Africa branch of ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability – and the African Circular Economy Network (ACEN) who brought together over 35 co-authors and contributors from across the continent and beyond. In a joint effort, stretching over almost half a year, the circular economy and urbanization experts co-authored the first draft of this paper focusing on the opportunities and barriers to more circular cities in Africa. They identify seven key considerations that require specific attention, seven resource systems to be looked at in depth, and seven key actions that are needed to improve the viability of circular strategies in Africa’s cities.

The circular economy concept is often rooted in case studies and theory that emerge from the Global North.

In Africa, circular economy is typically promoted by external actors supporting development in African contexts, but has yet to become a mainstream concept internally in urban development. The paper explains that small projects, private sector initiatives, or waste management processes usually implement circular practices in African cities; at the same time, some new networks and government entities have started interpreting the circular economy and begun to “establish governance and finance frameworks to support its implementation and regulation.”

The co-authors insist that circular economy principles need to be tailored to address pressing African developmental challenges: “… the starting point … should be citizen-focused, implemented with attention to social equity, quality of life, alternative infrastructure design, and service delivery.” For Africa’s cities to become more livable and sustainable, circular practices have a lot to offer, with seven key considerations requiring specific attention:

The discussion paper expands those seven considerations with a deeper look at seven resource systems and their respective “circular opportunities”:

For each of these seven systems, the authors identify and explore barriers, enablers and opportunities. In the Buildings & Construction Systems in African cities, for example, it provides concrete cases from South Africa, Egypt, Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda, in which existing policies form a systemic barrier to more circular and sustainable approaches. Yet there are still issues with leadership. While governments are the biggest developers in African cities, most government systems and processes of procurement do not promote sustainable practices in doing so.

The discussion paper suggests a multitude of possible solutions and opportunities for each resource system –identifying and elaborating seven key actions that are actually needed to improve the viability of circular economy strategies in African cities:

These provide food for thought for developers, urban planners, policy-makers and public and private finance. While the discussion paper is still in the draft stage, it was already discussed in November 2020 in a lively online workshop with over 150 participants. Comments from that workshop are currently being incorporated and a final version of the paper is expected in 2021.

At least three questions remain:

Millions of inhabitants in Africa’s cities expect answers, and they can’t wait until 2050.